Tag: COVID-19

Elective Surgery and Anesthesia for Patients after COVID-19 Infection

January 23, 2022 6:03 pm

ASA and APSF Joint Statement on Elective Surgery and Anesthesia for Patients after COVID-19 Infection is also available for download (PDF)

Since hospitals are able to continue to perform elective surgeries while the COVID-19 pandemic continues, determining the optimal timing of procedures for patients who have recovered from COVID-19 infection and the appropriate level of preoperative evaluation are challenging given the current lack of evidence or precedent. The following guidance is intended to aid hospitals, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and proceduralists in evaluating and scheduling these patients. It is subject to change as new evidence emerges.

In general, all non-urgent procedures should be delayed until the patient has met criteria for discontinuing isolation and COVID-19 transmission precautions and has entered the recovery phase. Elective surgeries should be performed for patients who have recovered from COVID-19 infection only when the anesthesiologist and surgeon or proceduralist agree jointly to proceed.

What determines when a patient confirmed to have COVID-19 is no longer infectious?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides guidance for physicians to decide when transmission-based precautions (e.g., isolation, use of personal protective equipment and engineering controls) may be discontinued for hospitalized patients or home isolation may be discontinued for outpatients.

Patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, as confirmed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing of respiratory secretions, may be asymptomatic or symptomatic. Symptomatic patients may be further sub-classified into two groups depending upon symptom severity. Table 1 provides definitions of these COVID-related illness levels of severity.

- Patients with mild to moderate symptoms* (generally those without viral pneumonia or oxygen saturation below 94 percent)

- Patients who experienced severe or critical illness** due to COVID-19 (e.g., pneumonia, hypoxemic respiratory failure, septic shock).

Severely immunocompromised patients***, whether suffering from asymptomatic or symptomatic COVID-19, are considered separately.

Current data indicate that, in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, repeat RT-PCR testing may detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA for a prolonged period after symptoms first appear. However, in these patients, replication-competent virus has not been recovered after 10 days have elapsed following symptom onset. Considering this information, the CDC recommends that physicians use a time- and symptom-based strategy to decide when patients with COVID-19 are no longer infectious.

For patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection who are not severely immunocompromised and experience mild to moderate symptoms*, the CDC recommends discontinuing isolation and other transmission-based precautions when:

- At least 10 days have passed since symptoms first appeared.

- At least 24 hours have passed since last fever without the use of fever-reducing medications.

- Symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath) have improved.

For patients who are not severely immunocompromised and have been asymptomatic throughout their infection, isolation and other transmission-based precautions may be discontinued when at least 10 days have passed since the date of their first positive viral diagnostic test.

In approximately 95 percent of severely or critically ill patients (including some with severe immunocompromise), replication-competent virus was not present after 15 days following the onset of symptoms. Replication-competent virus was not detected in any severely or critically ill patient beyond 20 days after symptom onset.

Therefore, in patients with severe to critical illness** or who are severely immunocompromised***, the CDC recommends discontinuing isolation and other transmission-based precautions when:

- At least 10 days and up to 20 days have passed since symptoms first appeared.

- At least 24 hours have passed since the last fever without the use of fever-reducing medications.

- Symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath) have improved.

Consultation with infection control experts is strongly advised prior to discontinuing precautions for this group of patients. Clinical judgment ultimately prevails when deciding whether a patient remains infectious. Maintaining transmission-based precautions and repeat RT-PCR testing may be appropriate if clinical suspicion of ongoing infection exists. The utility of repeat RT-PCR testing after improvement in symptoms is unknown as patients will frequently remain at least intermittently positive for weeks to months.

If a patient suspected of having SARS-CoV-2 infection is never tested, the decision to discontinue transmission-based precautions can be made using the symptom-based strategy described above.

Other factors, such as advanced age, diabetes mellitus, or end-stage renal disease, may pose a much lower degree of immunocompromise; their effect upon the duration of infectivity for a given patient is not known.

Ultimately, the degree of immunocompromise for the patient is determined by the treating provider, and preventive actions are tailored to each individual and situation.

What is the appropriate length of time between recovery from COVID-19 and surgery with respect to minimizing postoperative complications?

The preoperative evaluation of a surgical patient who is recovering from COVID-19 involves optimization of the patient’s medical conditions and physiologic status. Since COVID-19 can impact virtually all major organ systems, the timing of surgery after a COVID-19 diagnosis is important when considering the risk of postoperative complications.

There are limited data now that address timing of surgery after COVID-19 infection. One study found a significantly higher risk of pulmonary complications within the first four weeks after diagnosis (1). An upper respiratory infection within the month preceding surgery has previously been found to be an independent risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complications (2). Patients with diabetes are more likely to have severe COVID-19 disease and are more likely to be hospitalized (3,4). Studies conducted during the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic found that pulmonary function continues to recover up to three months after ARDS (5).

Given this current knowledge base, wait times before surgery can be reasonably extrapolated and are a suggested starting point in the preoperative evaluation of the COVID-19-recovered patient.

The timing of elective surgery after recovery from COVID-19 utilizes both symptom- and severity-based categories. Suggested wait times from the date of COVID-19 diagnosis to surgery are as follows:

- Four weeks for an asymptomatic patient or recovery from only mild, non-respiratory symptoms.

- Six weeks for a symptomatic patient (e.g., cough, dyspnea) who did not require hospitalization.

- Eight to 10 weeks for a symptomatic patient who is diabetic, immunocompromised, or hospitalized.

- Twelve weeks for a patient who was admitted to an intensive care unit due to COVID-19 infection.

These timelines should not be considered definitive; each patient’s preoperative risk assessment should be individualized, factoring in surgical intensity, patient co-morbidities, and the benefit/risk ratio of further delaying surgery.

Residual symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and chest pain are common in patients who have had COVID-19 (6,7). These symptoms can be present more than 60 days after diagnosis (7). In addition, COVID-19 may have long term deleterious effects on myocardial anatomy and function (8). A more thorough preoperative evaluation, scheduled further in advance of surgery with special attention given to the cardiopulmonary systems, should be considered in patients who have recovered from COVID-19 and especially those with residual symptoms.

Is repeat SARS-CoV-2 testing needed?

At present, the CDC does not recommend re-testing for COVID-19 within 90 days of symptom onset (9). Repeat PCR testing in asymptomatic patients is strongly discouraged since persistent or recurrent positive PCR tests are common after recovery. However, if a patient presents within 90 days and has recurrence of symptoms, re-testing and consultation with an infectious disease expert can be considered.

Once the 90-day recovery period has ended, the patient should undergo one pre-operative nasopharyngeal PCR test ideally ≤ three days prior to the procedure.

References

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. Delaying surgery for patients with a previous SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. BJS 2020; 107: e601–e602. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.12050

- Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology 2010;113:1338. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fc6e0a

- Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J 2020. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020

- Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1966 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1966.

- Hsieh M-J, Lee W-C, Cho H-Y, et al. Recovery of pulmonary functions, exercise capacity, and quality of life after pulmonary rehabilitation in survivors of ARDS due to severe influenza A (H1N1) pneumonitis. Influenza and other respiratory viruses. Apr 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12566

- Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ., et al. Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network – United States, March-June 2020. MMWR 2020 Jul 31;69(30):993-998. https://dx.doi.org/10.15585%2Fmmwr.mm6930e1

- Carfi A, Bernabei R, Landi F., et al. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA July 9, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603

- Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, et al. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(11):1265-1273. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html

Accessed Oct 28, 2020

Table 1: Definitions for Severity Levels of COVID-Related Illness

The studies used to inform the guidance in this joint statement do not clearly define “severe” or “critical” illness. The definitions in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines (cited under references below) are suggested to categorize disease. The highest level of illness severity experienced by the patient at any point in their clinical course should be used.

* Mild Illness: Signs and symptoms of COVID-19 (e.g., fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain) without shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging.

* Moderate Illness: Evidence of lower respiratory disease by clinical assessment or imaging and oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≥94 percent on room air at sea level.

** Severe Illness: Respiratory rate >30 breaths per minute, SpO2 <94 percent on room air at sea level (or, for patients with chronic hypoxemia, a decrease from baseline of >3 percent), a ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) <300 mmHg, or lung infiltrates involving >50 percent of the lung fields.

** Critical Illness: The presence of respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction.

*** The studies used to inform this guidance did not clearly define “severely immunocompromised.” For the purposes of this guidance, “severely immunocompromised” refers to patients:

-

- Currently undergoing chemotherapy for cancer.

- Within 1 year of receiving a hematopoietic stem cell or solid organ transplant.

- Having untreated HIV with a CD4 T lymphocyte count <200.

- Having a combined primary immunodeficiency disorder.

- Treated with prednisone >20mg/day for more than 14 days.

Reference sources from CDC and NIH websites as of 22 Sept 2020:

Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html

Overview of testing

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/testing-overview.html

Discontinuation of Transmission-Based Precautions and Disposition of Patients with COVID-19 in Healthcare Settings (Interim Guidance)

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/disposition-hospitalized-patients.html

Duration of Isolation and Precautions for Adults with COVID-19

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fcommunity%2Fstrategy-discontinue-isolation.html

National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines

https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/whats-new/

A GUIDE TO COVID-19 TESTS FOR THE PUBLIC

January 23, 2022 5:38 pm

THE MAIN TESTS AVAILABLE FOR COVID-19

VIRUS STRUCTURE

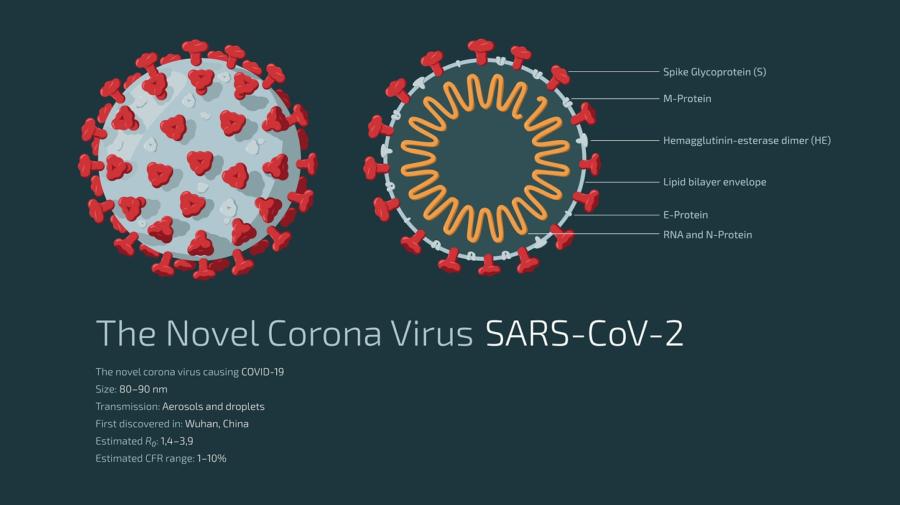

To understand testing methods, it is helpful to understand the structure of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease COVID-19.

The virus is composed of a core made up of nucleic acid (nucleic acids are what makes up the virus’s genetic code) in the form of RNA, surrounded by a coat called the envelope which contains various proteins. Spikes formed of a protein called the S (spike) protrude from the envelope. It is the S protein that attaches to cells of the human respiratory tract.

To understand testing methods, it is helpful to understand the structure of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease COVID-19.

The virus is composed of a core made up of nucleic acid (nucleic acids are what makes up the virus’s genetic code) in the form of RNA, surrounded by a coat called the envelope which contains various proteins. Spikes formed of a protein called the S (spike) protrude from the envelope. It is the S protein that attaches to cells of the human respiratory tract.

TESTING

The tests commonly available for SARS-CoV-2 can detect either:- the RNA − detected by the PCR test

- the surrounding proteins − detected by the rapid lateral flow devices

- the human body’s response to the virus – detected by antibody tests.

PCR TESTINGNUCLEIC ACIDS ARE WHAT MAKES UP THE VIRUS’S GENETIC CODE

PCR tests detect the virus’ RNA. These tests are normally carried out in a laboratory using a swab of the nose and/or throat. PCR tests can detect very tiny amounts of RNA, meaning they are extremely sensitive. They are the best test for current infection. Patients with COVID-19 usually start to become positive by PCR testing a day or two before symptoms start and will continue to test positive by PCR afterwards for some time. Repeat PCR once a diagnosis has been made is not necessary. The period the patient must isolate for is defined by time from the start of symptoms or, if there are no symptoms, from the first positive test. Current UK policy is that patients must self-isolate for ten days after this time.WHEN SHOULD I HAVE A PCR TEST?

- If you currently have symptoms that may indicate COVID-19, this is the test you should have to diagnose the infection.

- If a lateral flow test is positive. The purpose of the PCR test is to confirm the diagnosis, since it is a more accurate test than the lateral flow test.

IS A PCR TEST ACCURATE?

PCR is the most accurate test available for current infection. In a person with symptoms, a positive PCR test is likely to accurately indicate infection. If a person has symptoms suggesting infection but a negative PCR test, doctors may decide to repeat the test if they still suspect infection (e.g. in hospitalised patients).LATERAL FLOW TESTS

These are the rapid tests that are used in the community. They are convenient because they can give a result within 30 minutes and do not need a laboratory. They detect proteins from the virus, not RNA. They use a swab of the nose and/or throat and are carried out on a small flat plastic device like a pregnancy test. These tests are very different from PCR. They are not suitable for diagnosing individual patients who suspect they may be infected because they have symptoms. People with symptoms need a PCR test. Lateral flow tests are intended for picking up additional infected cases who would otherwise be missed because they don’t have any symptoms.WHEN SHOULD I HAVE A LATERAL FLOW TEST?

- You should only have this test if you don’t have any symptoms and have been invited to take one as part of an exercise to identify infected people without symptoms.

ARE LATERAL FLOW TESTS ACCURATE?

These tests are not as sensitive as PCR. They are simply a convenient way of picking up a proportion of undiagnosed people who have no symptoms. The way to look at these tests is that every additional positive case picked up is a bonus, preventing further unknown transmission of the virus. If a person tests positive with these tests, they need to confirm this by having a more accurate PCR. In the meantime, they must self-isolate. If these tests are negative, the person may or may not be infected and that person must continue to take the usual precautions such as hand washing, wearing a mask and social distancing. A negative lateral flow test should not be used to rule out infection or indicate that it is safe to do something such as visit relatives. You can read more about the accuracy of lateral flow tests here.ANTIBODY TESTS

These tests detect the body’s response to a previous infection, by looking for antibodies that the body has produced. It takes some time after infection for the body to produce antibodies. So, antibody tests are not suitable for diagnosing people at the time they have symptoms. They are useful for finding out if someone has been infected in the past. This is useful, for example, for studying how many people in a population have been infected. It is not known for how long after infection antibody tests remain positive. Levels of antibody are likely to decline with time, over months or years.WHEN SHOULD I HAVE AN ANTIBODY TEST?

- You might be asked to have an antibody test as part of a study to see how many people have been infected in the past.

- In future, if a doctor wanted to know if you had been infected in the past, they might perform an antibody test.

LAMP AND LAMPORE TESTING

Like RT-PCR, LAMP and LampORE tests detect the viral RNA. They have the advantage of being able to use saliva as a sample, as well as swabs. Recently LamPORE has been deployed for local community testing in some locations. This test can be carried out in mobile laboratories around the country. LamPORE tests have high accuracy. They can be used for people with or without symptoms, but they are currently being deployed in the UK to detect people without symptoms in the community. As these tests are more accurate than lateral flow tests, positive tests do not require a confirmation by PCR. Copied: Source https://www.rcpath.org/profession/coronavirus-resource-hub/guide-to-covid-19-tests-for-members-of-the-public.htmlCovid 19 Response

January 19, 2022 9:17 am

1. Introduction:

The first case of COVID-19 was detected on December 31, 2019 (Guan et al., 2020). In a rapid series of events, the virus was identified, its genomics mapped, testing developed, and a working model for containment became available worldwide. There is a significant body of scientific evidence on how to control a pandemic in the published literature (Allot et al., 2017; WHO, 2009; World Health Organization, 2009; Yamamoto, 2013). And yet, the communication from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) appeared disjointed, confusing, and contradictory at times. Given the fluid nature of the newly identified infectious agent, CDC should have predicted that the shared information’s uncertain nature may be perceived as organizational incompetence (J. S. Ott & Shafritz, 1994)and unreliable (Hyer et al., 2007). The changing narrative led to diminished credibility, and the perceived void in authority was occupied by alternative reality providers advocating measures for pandemic control with no scientific proof. The public health organization from WH to CDC failed to distinguish between the message delivered and what was perceived by the public. They furthermore did not recognize the need for corrective actions when the messaging gap widened. The geopolitical implication of the COVID-19 pandemic has been discussed in the literature (Directorate General for External Policies of the Union, 2020), and it appears that most local and regional recommendations were influenced based on socioeconomic and political factors. The contradictions received by the public fueled the skepticism. Lack of leadership at the levels of the administration of the US government is examined in this report. Changes to existing theoretical frameworks are needed to accommodate the rapidly evolving 21st-century digital information and communication platforms and the widening perception of delivered public health messages. Link to Full ArticleShort and Long term Effects of Conflicts on Healtcare

October 30, 2021 12:26 pm

Introduction:

The health of the society is the collective sum of the individual health of its population; physical and mental health are equally important in overall well-being (Kindig & Stoddart, 2003). A conflict causes significant destruction of life and property. For those who survive the initial assault, individually and collectively, the outlook for short and long-term physical and mental health is multifactorial and regretfully grave. Regardless of the state of an individual’s health and the healthcare delivery system, a conflict is a significant added burden that most middle- and low-income countries can afford the least (Jacob, 2009; Mills, 2014). Armed conflict has become a global health issue that has led to casualties and injuries, disrupted public health systems and social cohesion, and created displacement, poverty, and unemployment, all having long-term consequences that are also intergenerational (Samman E et al., 2018). In most low- and middle-income countries, the health care systems are grossly underfunded, relatively frequently underdeveloped, and ill-equipped to respond to the added stress caused by a conflict (Orach, 2009). The limitation of capacity in the health care delivery system is unsurmountable since most of those displaced are internally displaced in a conflict zone or to a neighboring county (Murshidi et al., 2013). The recipient countries of the refugees are more likely to be of the same low- or middle-income country level (Huang C & Graham J, 2018). The impact on the health care systems goes far beyond the conflict zone and affects the entire population dependent on the fragile system (Johnson, 2017). The short-term effects may be apparent in the destruction of the facilities and displacement of the healthcare workers. The long-term impact may be more subtle and multifactorial. Lack of resources (supply and personal) (Brundtland, 2000) and inadequate recognition and response to the stress on the health care staff (Finnegan et al., 2016) results in a downward spiral of access to care and quality of care in a conflict zone. The short-term physical injuries, the disabilities that follow, and the long-term effect of the psychological impact of a conflict burden the subset of the ill-equipped society in the middle- or low-income countries (Garry & Checchi, 2020). Women, children, the elderly, disabled, and injured require protection, care, and support where its least available (Jahanshahi et al., 2020; Macksoud & Aber, 1996). Moreover, the traumas caused by conflict on the children are long-lasting and may span to adulthood with lifelong consequences in their education, earning potential, social integration, and ultimately their health (Kaminer et al., 2016).

The different variables of conflict and health determinants, short and long-term, will be discussed with examples. Finally, the specific conflict of Nagorno-Karabakh will be discussed.

Definitions:

Health was initially defined by WHO in 1946 as “…a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, not merely an absence of disease or infirmity.” However, this definition has been a subject to evolving interpretation by many in different disciplines (Brüssow, 2013; Huber et al., 2011). Therefore, we will consider a broad definition of health as physical, mental, and social well-being encompassing the broader health determinants (Dahlgren G & Whitehead M, 1991).

Conflicts result in death and destruction and should be considered a public health problem affecting individuals in the conflict zone (C. J. L. Murray et al., 2002, 2016).

The short- and long-term effects of the conflict will be discussed at the individual and population levels. It is essential to acknowledge that the descriptive nature of the term “short” and “long term” is vague in this setting. Unlike specific medical disciplines, there is no clear definition for the transition between the two time frames.

Short term impact of Conflict on Individual and Population health:

Individual and population health are intricately intertwined; it is a continuous spectrum where collective individual health becomes population health (Ashraf et al., 2009; Bauer, 2019; German & Latkin, 2012). Individual health is discussed in the context of an individual’s medical care, whereas population health is in public health setting (Arah, 2009). All health determinants affecting individual health will have implications on the population’s health. An individual’s health is determined by several variables, including physical health, employment, shelter, social and family structure. A conflict will have a broad short-term implication on individual health, whereas population health effects present long-term symptoms (Figure 1)[1].

An individual in any health status will have 1-Preventive (vaccination, screening mammography or colonoscopy, well-child checkup, pre-natal) or 2-Therapeutic (treatment for NCD’s, injuries due to motor vehicle accidents, sports injury, mental health, STD’s, substance dependence) healthcare requirements (Doocy et al., 2015; Pavli & Maltezou, 2017). Limited data and follow-up have shown that the pre-conflict health delivery infrastructure will determine the level of care that can be delivered post-conflict at an individual level, with implications for the population at large (Afzal & Jafar, 2019). The same is true for other determinants of health, where the pre-conflict level will predict the post-conflict state (Spiegel et al., 2010). Significant attention is given to the immediate care needed in a conflict zone. Research has shown that psychological distress, preexisting NCD’s, reduced physical activity, change in the living arrangements leading to smoking and alcohol use, violence and insecurity in refugee camps, and discriminations in host countries all have long term effects that receive much less if any attention (B. Roberts et al., 2012).

The outcome of physical injury, direct (penetrating, non-penetrating) or indirect (building collapse) because of a conflict, will depend on the existing infrastructure. Military capabilities aside, a rocket launch from Occupied Palestinian Territory (oPt) to Israel has a much different outcome than a counterattack from Israel to Gaza. The disparity between the preexisting health of these two neighboring populations has been described (Rosenthal, 2021). However, the outcome of the inflicted attack may be as much a function of a superior robust trauma system in Israel and lack thereof the same in oPt (Borgohain & Khonglah, 2013). The psychological impact on the long-standing conflict between Israel and oPt has also been documented (Rosenthal, 2021). The poor socio-economic condition at the oPt is reflected in the higher Standardized Mortality Rate (SMR) for the population at oPt compared to Israel for most of the NCD (Rosenthal, 2021). The higher SMR is an example of how poor individual health in a conflict zone translated to poor population health. The distinction between short-term and long-term health is difficult to distinguish; however, the long-term effect on children is documented (Jürges et al., 2020).

An employed individual with family housing, adequate nutrition, sanitation, clean water, a school for children, and safe living condition free of violence may be able to withstand the short-term insult of a conflict; however, the long-term outcome in the context of psychological, safety, and security (food, education, physical, family) is much less predictable (Afzal & Jafar, 2019).

An individual may suffer an injury during a conflict. The physical injury may result in disabilities that will translate to long-term disabilities. The psychosocial, economic, and physical consequences may be life ling not only affecting the injured but also the family at large. An initial injury requires significant resources for treatment in the form of supply, personal, and logistics. However, very little is invested in the long-term effect of an acute injury, both the physical and mental (post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD). The unique nature of the injury may also present specific challenges for short- and long-term treatment options. Chemical and biological weapons (barred by international norms) require highly specialized settings to avoid healthcare exposure and care. In many conflict-affected regions, women and children bear the shortest- and long-term impact of conflict (Bendavid et al., 2021; Murthy & Lakshminarayana, 2006), as they tend to lack access to maternal and child health (MCH) services, vaccination services, face malnutrition, and various forms of exploitation such as rape gender-based violence, and discrimination. The health providers allocate the available medical resources towards those suffering from severe injuries, leading to de-prioritizing MCH services, which risks poor health outcomes that may have short-term and long-term consequences (Devakumar et al., 2015). Regions facing conflict usually have higher neonatal morbidity and mortality rates because of poor nutrition, lack of access to adequate healthcare, maternal stress, and reduced breastfeeding rates (Sapir, 1993). Syrian women, for example, used to enjoy access to standard antenatal care during pre-conflict periods, and close to 96% of birth deliveries were usually with the assistance of a skilled midwife (Kherallah et al., 2012; Samari, 2017). However, this has changed post-conflict, with many having higher rates of poor outcomes from pregnancy, including low birth weights, an increase in fetal mortality, antenatal complications, and occurrences of premature labor (Samari, 2017). The effect of poor pre-and post-natal health of a child may have dire consequences which will impact all aspects of the individual and population life short and long term. These individual short-term health outcomes resulting from a conflict have broad-reaching short- and long-term effects on the individual, society, and population.

The loss of life of young men has a long-term detrimental outcome for the surviving family. The population in a conflict zone may also be directly involved in the injuries caused by bullets, shrapnel, bombing, resulting in collapse buildings and Chemical weapons. Secondary injuries may include non-recoverable injuries due to severity or lack of adequate and effective healthcare personnel to treat the injuries. Destruction of healthcare facilities, housing infrastructure all contributes to delayed health delivery. Secondary injuries in the form of water pollution possibly result in communicable diseases, malnutrition due to lack of food, and breakdown of the infrastructure roads and bridges to access the food. Immediate psychological injuries, including post-traumatic stress disorder, can have short and long lifelong consequences (Hynie, 2017). The same is true of those who have been internally displaced within the same social and cultural environment (B. Roberts et al., 2009). As conflicts persist, the health care spending decreases as the military spending raises, further hindering the population health care (Fan et al., 2018). The allocation of the resources results in further draining of the health care infrastructure.

Conflicts:

Most of the Conflicts in the world are carried over in the middle to low-income countries (Vestby et al., 2021). The healthcare burden in those countries includes infectious communicable and non-communicable diseases. Lack of reliable water sources, poor sanitation, poor education, and social safety networks and housing are additional contributors to the health caused by the destruction caused by conflicts. Most middle- to low-income countries have a population with a premature death rate and lower life expectancy (Ho & Hendi, 2018; Islam et al., 2018) compared to high-income countries. Most conflict involves primarily young and middle-aged men who may succumb to direct injuries.

Causes of conflicts are multifactorial. The incidence of conflicts has been rising since 1950. Economic and social inequalities, food insecurity, educational and health inequities, poverty, political, cultural, religious, and ethnic frictions are contributing causes for conflicts (Burns & Devillé, 2017; Džuverovic, 2013; Lichbach, 1989). Since the 1950s, there have been more intense conflicts within and amongst countries (Stewart, 2002). The additional distressing statistic is that nearly 80-90% of the victims of the conflicts are now civilians. This figure includes those directly killed or injured in the conflict and those who succumb to the indirect effects of the conflict, including infectious diseases, NCD (due to lack of adequate medical care), malnutrition both as refugees and IDP’s (A. Roberts, 2010). Quite commonly, a vicious cycle of conflict is formed intergenerationally (Devakumar et al., 2014). As a result, the population and society get entrapped in a loop of continued conflict. The inability to escape the cycle of conflict and violence is due to the failure to resolve and break away from the underlying causes (Mitchell, 2019). A conflict breaks the root cause of the causes of social determents of health, some noticed in a concise time frame and most reflected, at times an unnoticed long term (Braverman & Gottlieb, 2014).

Case Discussion: Armenia, The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict.

Nagorno-Karabakh (NK) is a predominantly Armenian community that Armenia and Azerbaijan have governed since early 1900. Armenia became independent in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union. Armenia inherited a centralized health care system underfunded, understaffed, and highly specialized state-run district hospitals (Hovhannisyan, 2004; Torosyan et al., 2008a). Since early 2000, it has been undergoing a slow transition, emphasizing preventive primary medical care and less inpatient centralized hospitalization. There has been a steady transition toward a form of universal health care with a private out-of-pocket (OOP) model (Chukwuma et al., 2021). Health Systems in Transition (HiT) is a slow and complicated process to implement (Erica Richardson, 2013). As part of the health care delivery system in Armenia, these changes have been perceived negatively by the citizens of Armenia (Harutyunyan & Hayrumyan, 2020). The individual’s lack of trust in the health care system may have been a critical issue to the addition of the conflict and the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first case of Covid was reported officially in Armenia on February 29, 2020 (Reuter Staff, 2020).

Pre Covid (March 11, 2020) and before the onset of the Conflict (September 27, 2020) in NK and Azerbaijani invasion, the health care system was somewhat functioning as an OOP model, with obstetrical and pediatric care entirely funded by the central government (Erica Richardson, 2013). The conflict resulted in between 90,000 to 120,000 ethnically Armenian from NK to Armenia (Connelly A, 2020). With the massive influx of refugees to Armenia, the social, educational, community, and health services were overwhelmed. Availability of social services, housing, nutritional support, preventive care was strained with little buffer available in the system. The displaced refugees from NK to Armenia had significant preexisting health care needs, probably due to inadequate preventive and primary care access in NK (Project HOPE, 2020).

The immediate short-term healthcare needs of the NK residents escalated as the hospitals became a target of the bombing and rocket attacks in violation of international norms (Hugh Williamson, 2021).

When the focus in Armenia was the care of displaced Armenians from NK, caring for the injured, and providing supportive services to the displaced and disabled, COVID-19 was not seen or be considered a priority (Balalian et al., 2021). The conflict added complexity to culture and society, skeptical of the preventive measures against COVID-19 and vaccination efforts (Badalyan et al., 2021). The skeptical public was only reinforced with false information propagated by media supported by the US government (Tatev Hovhannisyan, 2020). The skepticism against COVID-19 contrasts with the very high vaccination rate for other childhood infections as tracked (WHO-Europe, 2019). Overburdening of the system is an example of how a fragile society, in a LIC, has little capacity to absorb the insult of a conflict. Before the Conflict, Armenia faced much public health, political, economic, and international relations challenges. Systemic changes initiated by the Armenian Ministry of Health (MOH) in the late 1990s resulted in some index health quality measured show improvement; however, the health indicators had not developed at the desired pace predicted (Torosyan et al., 2008b). In the health sector, NCD, smoking, rural poverty, and unemployment contribute to poor predictive outcomes of population health (S. Murray, 2006; Nowack, 1991). The short- and long-term health implications of the NK conflict directly affected those involved and the host for the refugees (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2020). Short- and long-term psychological trauma of the conflict and the stress of displacement, lack of employment, and the long-term uncertainty for children, superimposed on the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, should not be overlooked by the host community (Markosian, Khachadourian, et al., 2021; Markosian, Layne, et al., 2021). The unresolved stress of displacement, long-term, can exacerbate the risk of poor health for women, children, and the elderly due to violence (Bradley, 2018).

The World bank changes its classification for the income grouping of the countries in 2018 (World Bank Data Team, 2018). Initially listed as Low–To middle-income country, Armenia was reclassified and Upper–Middle-income country (World Bank, 2018). The change in the income level classification is reflective of an expanding economy in transition. The long-term effect of the conflict on the population is the indirect result of the economic loss experienced. International Monetary fund projects a -7.25% contraction in GDP due to the combination of the conflict, the influx of refugees, and the second surge of the Covid-19. The significant contraction of the economic activity is due mainly to the loss of tourism and travel of Armenian in diaspora in 2021-2022 (IMF Staff, 2020). The reduced income will significantly impact government spending and the allocation of the fund in the healthcare system.

The cultural barriers to care should also be emphasized. The long-term mental health concerns for the displaced, injured, and disabled would need to be dealt with (Soghoyan et al., 2009). As with most eastern cultures, mental health and psychological disorders are frequently minimized, underdiagnosed, and inadequately treated due to stigmatization by society (van Baelen et al., 2005). This dismissive approach may translate to policy, funding, and treatment policies that can hinder the individual and consequently population health. The inability to procure and maintain gainful employment and provide for one’s family due to untreated mental illness will result in poor health outcomes secondary to decreased earning potential, inability to maintain employment or cope with the stress (Khalema & Shankar, 2014).

Summary:

Conflicts, regardless of the underlying cause, affect the fiber of society. Education, employment, and family functions may be disrupted. In addition, housing loss, inadequate food, and sanitation are experienced by most in the zone of conflict, and healthcare delivery is interrupted. Insomnia, fear fatigue may set in quite quickly. These short-term effects will have long-term consequences individually and the population at large.

At an individual level, in addition to the potential direct injury (penetrating, non-penetrating crush, biologic and chemical, falling debris, shrapnel wounds, burn, broken bones), communicable and non-communicable disease (preexisting, undiagnosed) need to be addressed. The initial injury may lead to permanent physical disfigurement, loss of limb and function. In addition, mental health deterioration is seen quite frequently, presenting as insomnia, a sense of despair, and anger. As time progresses, even with improvement or resolution of some of the physical injuries, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression are examples of mental health conditions that set in.

At a population level, the initial injury is the destruction of infrastructure, population displacement, economic activity collapse, and social services. Then, as with the progression of the conflicts, the elements of a functioning society break down, including the health care delivery system.

Health care determinants are all affected in a conflict to varying degrees, whether short or long term, at individual or population level.

References:

Afzal, M. H., & Jafar, A. J. N. (2019). A scoping review of the wider and long-term impacts of attacks on healthcare in conflict zones. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 35(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2019.1589687

Arah, O. A. (2009). On the relationship between individual and population health. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 12(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-008-9173-8

Ashraf, Q. H., Lester, A., & Weil, D. N. (2009). WHEN DOES IMPROVING HEALTH RAISE GDP? NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 23, 157–204. https://doi.org/10.1086/593084

Badalyan, A. R., Hovhannisyan, M., Ghavalyan, G., Ter-Stepanyan, M. M., Cave, R., Cole, J., … Mkrtchyan, H. V. (2021). The Knowledge and Attitude of Physicians Regarding Vaccinations in Yerevan, Armenia: Challenges for COVID-19. MedRxiv, 2021.06.15.21258948. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.15.21258948

Balalian, A. A., Berberian, A., Chiloyan, A., Dersarkissian, M., Khachadourian, V., Siegel, E. L., … Hekimian, K. (2021). War in Nagorno-Karabakh highlights the vulnerability of displaced populations to COVID-19. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-216370

Bauer, U. E. (2019). Community Health and Economic Prosperity: An Initiative of the Office of the Surgeon General.Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 134(5), 472–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354919867727

Bendavid, E., Boerma, T., Akseer, N., Langer, A., Malembaka, E. B., Okiro, E. A., … Wise, P. (2021). The effects of armed conflict on the health of women and children. The Lancet, 397(10273), 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00131-8

Borgohain, B., & Khonglah, T. (2013). Developing and Organizing a Trauma System and Mass Casualty Management: Some Useful Observations from the Israeli Trauma Model. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research, 3(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.4103/2141-9248.109455

Bradley, S. (2018). Domestic and Family Violence in Post-Conflict Communities: International Human Rights Law and the State’s Obligation to Protect Women and Children. Health and Human Rights, 20(2), 123–136. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30568407

Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Reports, 129(1_suppl2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S206

Brinkman, H., & Hendrix, C. S. (2011). Food Insecurity and Violent Conflict : Causes , Consequences , and Addressing the Challenges. Challenges, (July).

Brundtland, G. (2000). THE WORLD HEALTH REPORT 2000. Geneva.

Brüssow, H. (2013). What is health? Microbial Biotechnology, 6(4), 341–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.12063

Burns, T. R., & Devillé, P. (2017). Socio-economics: The approach of social systems theory in a forty year perspective. Economics and Sociology, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2017/10-2/1

Chukwuma, A., Lylozian, H., & Gong, E. (2021). Challenges and Opportunities for Purchasing High-Quality Health Care: Lessons from Armenia. Health Systems & Reform, 7(1), e1898186. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2021.1898186

Connelly A. (202AD, November 30). Nagorno-Karabakh refugees see little chance of returning home after peace deal. Retrieved August 19, 2021, from https://www.politico.eu/article/nagorno-karabakh-refugees-see-little-chance-of-returning-home-after-peace-deal/

Dahlgren G, & Whitehead M. (1991). Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991) – Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute for future studies. Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/display/6472456

Devakumar, D., Birch, M., Osrin, D., Sondorp, E., & Wells, J. C. K. (2014). The intergenerational effects of war on the health of children. BMC Medicine, 12(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-12-57

Devakumar, D., Birch, M., Rubenstein, L. S., Osrin, D., Sondorp, E., & Wells, J. C. K. (2015). Child health in Syria: Recognising the lasting effects of warfare on health. Conflict and Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-015-0061-6

Doocy, S., Lyles, E., Roberton, T., Akhu-Zaheya, L., Oweis, A., & Burnham, G. (2015). Prevalence and care-seeking for chronic diseases among Syrian refugees in Jordan. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1097. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2429-3

Džuverovic, N. (2013). Does more (or less) lead to violence? Application of the relative deprivation hypothesis on economic inequality-induced conflicts. Croatian International Relations Review, 19(68). https://doi.org/10.2478/cirr-2013-0003

Erica Richardson. (n.d.). Health Systems in Transition : Armenia.

Fan, H. L., Liu, W., & Coyte, P. C. (2018). Do Military Expenditures Crowd-out Health Expenditures? Evidence from around the World, 2000–2013. Defence and Peace Economics, 29(7). https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2017.1303303

Finnegan, A., Lauder, W., & McKenna, H. (2016). The challenges and psychological impact of delivering nursing care within a war zone. Nursing Outlook, 64(5), 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2016.05.005

Garry, S., & Checchi, F. (2020). Armed conflict and public health: Into the 21st century. Journal of Public Health (United Kingdom), 42(3), E287–E298. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdz095

German, D., & Latkin, C. A. (2012). Social stability and health: exploring multidimensional social disadvantage. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 89(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9625-y

Harutyunyan, T., & Hayrumyan, V. (2020). Public opinion about the health care system in Armenia: findings from a cross-sectional telephone survey. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1005. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05863-6

Harutyunyan, T., & Hayrumyan, V. (2020). Public opinion about the health care system in Armenia: findings from a cross-sectional telephone survey. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1005. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05863-6

Ho, J. Y., & Hendi, A. S. (2018). Recent trends in life expectancy across high income countries: retrospective observational study. BMJ, 362, k2562. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2562

Hovhannisyan, S. G. (2004). Health care in Armenia. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 329(7465), 522–523. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7465.522

Huang C, & Graham J. (2018). Are Refugees Located Near Urban Job Opportunities? Washington DC. Retrieved from https://www.cgdev.org/publication/are-refugees-located-near-urban-job-opportunities

Huber, M., André Knottnerus, J., Green, L., Van Der Horst, H., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., … Smid, H. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ (Online), 343(7817). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4163

Hugh Williamson. (2021, February 26). wful Attacks on Medical Facilities and Personnel in Nagorno-Karabakh Print Search DONATE NOW February 26, 2021 8:00AM EST Available In English Русский Unlawful Attacks on Medical Facilities and Personnel in Nagorno-Karabakh. Retrieved August 22, 2021, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/26/unlawful-attacks-medical-facilities-and-personnel-nagorno-karabakh#

Hynie, M. (2017). The Social Determinants of Refugee Mental Health in the Post-Migration Context: A Critical Review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(5), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717746666

IMF Staff. (2020, December 11). IMF: Third Review, Armenia. Retrieved August 22, 2021, from https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/12/11/pr20371-armenia-imf-execboard-completes-3rd-review-under-sba-and-approves-us-36-9m-disbursement

Islam, M. S., Mondal, M. N. I., Tareque, M. I., Rahman, M. A., Hoque, M. N., Ahmed, M. M., & Khan, H. T. A. (2018). Correlates of healthy life expectancy in low- and lower-middle-income countries. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 476. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5377-x

Jacob, K. S. (2009). Public health in low- and middle-income countries and the clash of cultures. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(7), 509 LP – 509. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.086934

Jahanshahi, A. A., Gholami, H., & Rivas Mendoza, M. I. (2020). Sustainable development challenges in a war-torn country: Perceived danger and psychological well-being. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2077

Johnson, S. A. (2017). The Cost of War on Public Health: An Exploratory Method for Understanding the Impact of Conflict on Public Health in Sri Lanka. PLOS ONE, 12(1), e0166674. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166674

Jürges, H., Stella, L., Hallaq, S., & Schwarz, A. (2020). Cohort at risk: long-term consequences of conflict for child school achievement. Journal of Population Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00790-6

Kaminer, D., Eagle, G., & Crawford-Browne, S. (2016). Continuous traumatic stress as a mental and physical health challenge: Case studies from South Africa. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(8), 1038–1049. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316642831

Khalema, N. E., & Shankar, J. (2014). Perspectives on Employment Integration, Mental Illness and Disability, and Workplace Health. Advances in Public Health, 2014, 258614. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/258614

Kherallah, M., Alahfez, T., Sahloul, Z., Eddin, K. D., & Jamil, G. (2012). Health care in Syria before and during the crisis. Avicenna Journal of Medicine, 2(03). https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0770.102275

Kindig, D., & Stoddart, G. (2003). What is population health? American Journal of Public Health, 93(3), 380–383. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.3.380

Lichbach, M. I. (1989). An Evaluation of “Does Economic Inequality Breed Political Conflict?” Studies. World Politics, 41(4). https://doi.org/10.2307/2010526

Macksoud, M. S., & Aber, J. L. (1996). The War Experiences and Psychosocial Development of Children in Lebanon. Child Development, 67(1), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01720.x

Markosian, C., Khachadourian, V., & Kennedy, C. A. (2021). Frozen conflict in the midst of a global pandemic: potential impact on mental health in Armenian border communities. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(3), 513–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01996-5

Markosian, C., Layne, C. M., Petrosyan, V., Shekherdimian, S., Kennedy, C. A., & Khachadourian, V. (2021). War in the COVID-19 era: Mental health concerns in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211003940

Mills, A. (2014). Health Care Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(6), 552–557. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1110897

Mitchell, D. (2019). The cycle of insecurity: Reassessing the security dilemma as a conflict analysis tool. Peace and Conflict Studies, 26(2). https://doi.org/10.46743/1082-7307/2019.1586

Murray, C. J. L., King, G., Lopez, A. D., Tomijima, N., & Krug, E. G. (2016). Armed conflict as a public health problem: Assessing the public health impact of conflict. Annual Review of Public Health, Vol. 37.

Murray, C. J. L., King, G., Lopez, A. D., Tomijima, N., & Krug, E. G. (2002). Armed conflict as a public health problem. British Medical Journal. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7333.346

Murray, S. (2006). Poverty and health. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne, 174(7), 923. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.060235

Murshidi, M. M., Hijjawi, M. Q. B., Jeriesat, S., & Eltom, A. (2013). Syrian refugees and Jordan’s health sector. The Lancet, 382(9888), 206–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61506-8

Murthy, R. S., & Lakshminarayana, R. (2006). Mental health consequences of war: a brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 5(1), 25–30. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16757987

Nowack, K. M. (1991). Psychosocial predictors of health status. Work & Stress, 5(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379108257009

Orach, C. G. (2009). Health equity: challenges in low income countries. African Health Sciences, 9 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S49–S51. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20589106

Pavli, A., & Maltezou, H. (2017). Health problems of newly arrived migrants and refugees in Europe. Journal of Travel Medicine, 24(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tax016

Project HOPE. (2020, December 2). Health Issues Emerge as Top Concern Among Nagorno-Karabakh Refugees in Armenia. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://www.projecthope.org/health-issues-emerge-as-top-concern-among-nagorno-karabakh-refugees-in-armenia/12/2020/

Reuter Staff. (2020, February 29). Armenia reports first coronavirus infection. Retrieved August 16, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-armenia/armenia-reports-first-coronavirus-infection-idUSKBN20O1A5

Roberts, A. (2010). Lives and Statistics: Are 90% of War Victims Civilians? Survival, 52(3), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2010.494880

Roberts, B., Odong, V. N., Browne, J., Ocaka, K. F., Geissler, W., & Sondorp, E. (2009). An exploration of social determinants of health amongst internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. Conflict and Health, 3(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-3-10

Roberts, B., Patel, P., & McKee, M. (2012). Noncommunicable diseases and post-conflict countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(1), 2-2A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.11.098863

Roberts, B., Patel, P., & Mckeea, M. (2012). Noncommunicable diseases and post-conflict countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.11.098863

Rosenthal, F. S. (2021). A comparison of health indicators and social determinants of health between Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Global Public Health, 16(3), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1808037

Samari, G. (2017). Syrian Refugee Women’s Health in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan and Recommendations for Improved Practice. World Medical and Health Policy, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.231

Samman E, Lucci P, Zankr H.J., Simunovic A. T, & Stuart E. (2018). SDG Progress: Fragility, Crisis and Leaving No One Behind. London. Retrieved from https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/12424.pdf

Sapir, D. G. (1993). Natural and man-made disasters: The vulnerability of women-headed households and children without families. World Health Statistics Quarterly.

Soghoyan, A., Hakobyan, A., Davtyan, H., Khurshudyan, M., & Gasparyan, K. (2009). Mental health in Armenia. International Psychiatry, 6(3), 61–62. https://doi.org/10.1192/s174936760000059x

Spiegel, P. B., Checchi, F., Colombo, S., & Paik, E. (2010). Health-care needs of people affected by conflict: future trends and changing frameworks. Lancet (London, England), 375(9711), 341–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61873-0

Stewart, F. (2002). Root causes of violent conflict in developing countries. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 324(7333), 342–345. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7333.342

Tatev Hovhannisyan. (2020, May 28). Revealed: US-funded website spreading COVID misinformation in Armenia. Retrieved August 21, 2021, from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/us-money-armenia-misinformation-covid-vaccines/

Torosyan, A., Romaniuk, P., & Krajewski-Siuda, K. (2008). The Armenian healthcare system: recent changes and challenges. Journal of Public Health, 16(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-007-0160-y

Torosyan, A., Romaniuk, P., & Krajewski-Siuda, K. (2008). The Armenian healthcare system: recent changes and challenges. Journal of Public Health, 16(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-007-0160-y

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2020, December 3). Health Issues Emerge as Top Concern Among Nagorno-Karabakh Refugees in Armenia.

van Baelen, L., Theocharopoulos, Y., & Hargreaves, S. (2005). Mental health problems in Armenia: Low demand, high needs. British Journal of General Practice.

Vestby, J., Buhaug, H., & von Uexkull, N. (2021). Why do some poor countries see armed conflict while others do not? A dual sector approach. World Development, 138, 105273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105273

WHO-Europe. (2019). Routine immunization profile Armenia. Retrieved from https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/420505/ARM-ENG.pdf

World Bank. (2018). World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Retrieved August 22, 2021, from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519

World Bank Data Team. (2018, July 1). New country classifications by income level: 2018-2019. Retrieved August 22, 2021, from https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2018-2019

[1] Transition from individual to population with parallel short to long term effect. The individual health impact will persist for individuals’ long term, however the collective effect on population occurs long term.

Covid 19:Anesthesia, Weight Loss Surgery and Malnutrition

October 30, 2021 8:52 am

As the COVID-19 pandemic is charting its course into 2022, as health care providers, we have had to adapt and adjust to the transient and shifting environment. Testing for COVID-19 has been in place, and is now part of the standard for preoperative work-up. In addition, covid testing will likely be part of screening any surgical procedure for the foreseeable future.

The challenge of pandemic control is the large pockets of populations in the US and worldwide that do not have protection against the virus and are not vaccinated. Vaccination provides the only proven long-term protection against COVID-19 infection and its long-term persistent health effect. In addition, the complication rate reported in scientific journals is negligible compared to the complication and death rate from the COVID-19 infection.

There are implications of covid infection and general anesthesia published in peer-reviewed journals. The increased risk of general anesthesia after covid infection is related to the severity of the initial infection and the extent of the treatment required, and the persistence of the post covid symptoms, including shortness of breath, fatigue, and laboratory finding elevated inflammatory markers. Long after resolution of the acute COVID-19 symptoms, the most common persistent complaints are fatigue, shortness of breath, Joint and chest pain; and all these increase the risk of post-operative complications (Carfì et al., 2020)

The required delay for surgery may be as short as 2-4 weeks to as long as six months or longer if the persistent symptoms are present. Surgery may not be avoidable in a critical life-threatening situation and may be necessary even with a much-increased risk of complication (Collaborative, 2020). Recovery post-COVID-19 may not be complete with the resolution of the initial symptoms (Dexter et al., 2020)

Recent publications and scientific presentations have also shown the protection that weight loss surgery and maintained weight loss provide in those who come down with the COVID-19 infection (Aminian et al., 2021). However, the rate of weight gain, lack of weight loss is worse for weight loss surgical patients post COVID-19 disorder (Bullard et al., 2021; Conceição et al., 2021). Furthermore, patients with COVID-19 infection post weight loss are at a higher risk of malnutrition (di Filippo et al., 2021; Kikutani et al., 2021). Up to 40% of patients have malnutrition if hospitalized with COVID (Anker et al., 2021).

To summarize, Weight loss and weight loss surgery reduce the severity of the initial COVID-19 infection. However, it increases malnutrition risk, requiring nutritional support and surgical interventions in non-responsive cases.

REFERENCES:

Aminian, A., Fathalizadeh, A., Tu, C., Butsch, W. S., Pantalone, K. M., Griebeler, M. L., Kashyap, S. R., Rosenthal, R. J., Burguera, B., & Nissen, S. E. (2021). Association of prior metabolic and bariatric surgery with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in patients with obesity. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2020.10.026

Bullard, T., Medcalf, A., Rethorst, C., & Foster, G. D. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on initial weight loss in a digital weight management program: A natural experiment. Obesity, 29(9). https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23233

Conceição, E., de Lourdes, M., Ramalho, S., Félix, S., Pinto-Bastos, A., & Vaz, A. R. (2021). Eating behaviors and weight outcomes in bariatric surgery patients amidst COVID-19. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 17(6).

Di Filippo, L., De Lorenzo, R., D’Amico, M., Sofia, V., Roveri, L., Mele, R., Saibene, A., Rovere-Querini, P., & Conte, C. (2021). COVID-19 is associated with clinically significant weight loss and risk of malnutrition, independent of hospitalisation: A post-hoc analysis of a prospective cohort study. Clinical Nutrition, 40(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.10.043

Kikutani, T., Ichikawa, Y., Kitazume, E., Mizukoshi, A., Tohara, T., Takahashi, N., Tamura, F., Matsutani, M., Onishi, J., & Makino, E. (2021). COVID-19 infection-related weight loss decreases eating/swallowing function in schizophrenic patients. Nutrients, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041113

What does efficiency in healthcare delivery mean? Examples of two market failures

October 08, 2021 3:41 pm

Introduction:

Economic efficiency measures system performance (Enrique & Marta, 2020); the Healthcare delivery system (HCDS) is no different. In non-biologic systems, the efficiency can be measured and optimized since all variables are predictable. However, efficiency becomes a complex and possibly unachievable task in a biological environment such as HCDS. The summary report will define the efficiency and examine the limitation of achieving efficiency in the healthcare delivery system.

Definitions:

Efficiency measures the adeptness of a system allowing identification of the inadequacies and opportunities for improvement. Economic efficiency minimizes cost and maximizes production for profit (Petrou, 2014).

Healthcare is a commodity (Mills & Gilson, 2009). Increased need and limited resources, environment, illnesses are forces on an equilibrium of efficiency that requires flexibility. These are why economically competitive markets fail to achieve healthcare efficiency (Johansen & van den Bosch, 2017).

The concept of efficiency in health care has been described as Technical, Productive, and Allocative (Palmer & Torgerson, 1999). Extensive work has looked at special measures and populations for optimizing efficiency (Cylus & Papanicolas, 2016).

Efficient systems require predictable input, components, processes, and output, unlike efficiency in HCDS. The differences include:

- Biologic environments introduce variability in the system. Therefore, the HCDS efficiency will need to be flexible to diversity. Unfortunately, flexibility and efficiency counteract each other at industrial levels (Adler et al., 1999; AHRENS & CHAPMAN, 2004), and thus inefficiency is to be expected.

- Efficiency can be measured at two points:

- Efficiency of delivery

- Efficiency of outcome

Efficiency in HCDS means providing the most cost-efficient healthcare to those in need. As equity is a pillar of the HCDS, efficiency and equity are opposing forces (Guinness et al., 2011). Therefore, it is critical to have the broader determinants of health into consideration on HCDS. This broad spectrum of variables, individual level, and upstream factors (Dahlgren G & Whitehead M, 1991) will affect efficiency models applicable in one setting for a given population and inefficient in another (Hussey et al., 2009).

Healthcare Market:

The principle of maximizing profits applies to the four market types[1][2]. However, healthcare markets achieve Social Efficiency[3] and not economic efficiency (Folland & Goodman, 2013). This is due to Asymmetry of the information, Adverse selection, Moral hazard, Independent supply and demand stresses, and Externalities (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf, 2011).

Examples of Market Failure

At the onset of the pandemic, most governments, WHO assumed the costs of COVID-19 vaccination as they became available. Social media has disseminated incorrect information on vaccines (Lin et al., 2020; Wajahat Hussain, 2020). The Asymmetry of the information (AOI) has resulted in a sizable portion of the eligible population not being vaccinated (Coe et al., 2021; Malik et al., 2020). HCDS’s failure is a public relations problem and a breakdown in the trust of institutions (Soares et al., 2021).

Adverse selection (AS) compounds the AOI. There have been pockets of efficiency in vaccination with no equity for the world population (Mathieu et al., 2021).

This is due to the AOI and the structural inequities in HCDS (Hyder et al., 2021). Few countries are offering vaccine boosters, where most of the world’s population has not received any.

This is due to the AOI and the structural inequities in HCDS (Hyder et al., 2021). Few countries are offering vaccine boosters, where most of the world’s population has not received any.

References:

Adler, P. S., Goldoftas, B., & Levine, D. I. (1999). Flexibility Versus Efficiency? A Case Study of Model Changeovers in the Toyota Production System. Organization Science, 10(1), 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.1.43

Adler, P. S., Goldoftas, B., & Levine, D. I. (1999). Flexibility Versus Efficiency? A Case Study of Model Changeovers in the Toyota Production System. Organization Science, 10(1), 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.1.43

AHRENS, T., & CHAPMAN, C. S. (2004). Accounting for Flexibility and Efficiency: A Field Study of Management Control Systems in a Restaurant Chain*. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(2), 271–301. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1506/VJR6-RP75-7GUX-XH0X

Coe, A. B., Elliott, M. H., Gatewood, S. B. S., Goode, J. V. R., & Moczygemba, L. R. (2021). Perceptions and predictors of intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.04.023

Cylus, J., & Papanicolas, I. (2016). Health System Efficiency 46 How to make measurement matter for policy and management. London.

Dahlgren G, & Whitehead M. (1991). Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991) – Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute for future studies. Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/display/6472456

Enrique, B., & Marta, B. (2020). Efficacy, Effectiveness and Efficiency in the Health Care: The Need for an Agreement to Clarify its Meaning. International Archives of Public Health and Community Medicine, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.23937/2643-4512/1710035

Folland, S., & Goodman, A. (2013). The Economics of Health and Health Care. Oakland: Pearson.

Guinness, L., Wiseman, V., & Wonderling, D. (2011). Introduction to health economics. (2nd ed. /). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press.

Hussey, P. S., de Vries, H., Romley, J., Wang, M. C., Chen, S. S., Shekelle, P. G., & McGlynn, E. A. (2009). A systematic review of health care efficiency measures. Health Services Research, 44(3), 784–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00942.x

Hyder, A. A., Hyder, M. A., Nasir, K., & Ndebele, P. (2021). Inequitable COVID-19 vaccine distribution and its effects. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99(6), 406-406A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.21.285616

Johansen, F., & van den Bosch, S. (2017). The scaling-up of Neighbourhood Care: From experiment towards a transformative movement in healthcare. Futures, 89, 60–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2017.04.004

Lin, C. Y., Broström, A., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). Investigating mediated effects of fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 misunderstanding in the association between problematic social media use, psychological distress, and insomnia. Internet Interventions, 21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100345

Malik, A. A., McFadden, S. A. M., Elharake, J., & Omer, S. B. (2020). Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine, 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495

Mathieu, E., Ritchie, H., Ortiz-Ospina, E., Roser, M., Hasell, J., Appel, C., … Rodés-Guirao, L. (2021). A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(7), 947–953. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8

Mills, A., & Gilson, L. (2009). Health Economics for Developing Countries: A Survival Kit. Esocialsciences.Com, Working Papers.

Mwachofi, A., & Al-Assaf, A. F. (2011). Health care market deviations from the ideal market. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 11(3), 328–337. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22087373

Palmer, S., & Torgerson, D. J. (1999). Economic notes: definitions of efficiency. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 318(7191), 1136. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7191.1136

Petrou, A. (2014). Economic Efficiency. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (pp. 1793–1794). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_818

Soares, P., Rocha, J. V., Moniz, M., Gama, A., Laires, P. A., Pedro, A. R., … Nunes, C. (2021). Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9030300

Wajahat Hussain. (2020). Role of Social Media in COVID-19 Pandemic. The International Journal of Frontier Sciences, 4(2), 59–60. https://doi.org/10.37978/tijfs.v4i2.144

[1] Perfect competition, Monopoly, Oligopoly, Monopolistic competition

[2] Control of Total revenue (TR) and Cost (TC) to maximize profit

[3] An equilibrium point (Pareto Optimality) where Social Marginal Benefit (SMB) and the Cost (SMC) are equal

COVID Vaccines

March 05, 2021 3:50 pm

There are no known contraindications from a weight-loss surgical perspective to prevent a post-surgical patient from getting the COVID vaccines.

A patient who has had a Duodenal Switch, Lap Sleeve Gastrectomy, RNY Gastric Bypass, or revisions to Weight Loss Surgery should have the COVID vaccine. The vaccination should be avoided for a few weeks after surgery. For other possible contraindications, please consult your PCP.

Here is a summary of the vaccines and the details of each one approved as of the publication date.

Vitamin D, Immune Responce and COVID-19

January 26, 2021 6:45 pm

Vitamin A and Wound healing

December 21, 2020 9:37 am

Night Blindness – Vitamin A Deficiency

Nyctalopia (Night Blindness) An Early Sign of Vitamin A Deficiency with VideoA recent article discusses the types and function of vitamin A. As with the pandemic of COVID-19 continuous to stress our body and mind, we must stay vigilant with our nutritional status. Therefore, Vitamin supplements are critical in maintaining a robust immune system. For some, oral supplements are adequate; others may require injectable forms. If the oral supplements do not correct the vitamin A levels, please contact your primary care or our office to available vitamin A injections.

COVID – 19 Vaccine explained

December 07, 2020 9:10 pm